Robert Katz’s History of Modern Italy

An in-depth English language resource with an independent point of view.

|

TheBoot.it Robert Katz’s History of Modern Italy An in-depth English language resource with an independent point of view. |

| Home | About TheBoot | About Robert Katz | Forum | Issues | Time Capsules | Edizione Italiana | Contact TheBoot |

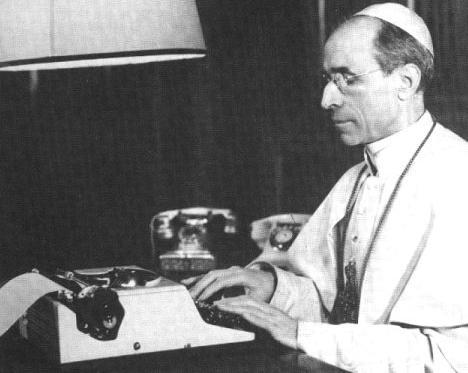

Pius XII Protests the HolocaustCould the wartime pope have prevented the Final Solution? The great debate that has accompanied the figure of Pope Pius XII throughout the second half of the twentieth century – and seems destined to intensify rather than recede as he continues to be moved by Vatican along the road to sainthood – concerns the position he took when faced with the unspeakable evil of Hitler’s systematic extermination of Europe’s Jews. There is no dispute, however, about what choice he made. He would remain publicly silent, never once uttering the word “Jew” in his many lamentations over the death and destruction caused by the global war. “There where the Pope would like to cry out loud and strong,” he confided to the Catholic bishops in Germany early in 1943, “it is rather restraint and silence that are often imposed on him.” This policy of silence had not been lightly assumed and it went beyond the Holocaust. He was among the first to learn that reports of Nazi genocide were not Allied propaganda, as many believed even until they began to breathe the flow of gas, but hideously true. Maintaining silence, however, was thought to be an imperative of his strategy to be seen by both the Western Allies and Germany as an impeccable neutral and so play a decisive role as peacemaker. Pius’s view that Stalin’s Russia was a greater menace than Hitler’s Germany and that he sought a general rapprochement in the West to contain if not roll back godless communism are elements of the controversy also not in dispute. Nor does anyone deny that the pope worked behind the scenes to provide sanctuary to persecuted Jews in religious institutions, including the Vatican itself, though the numbers of lives saved remain hotly contested, ranging from a documentable few thousand to much higher figures still lacking substantiation. But the question to ask, and herein lies the rub, is not about the thousands who to their great fortune found a rare hiding place in a Vatican enclave but about the millions who were sucked into the machinery of death and came out a corpse at the other end. What did silence mean for them? One cogent answer – “the long and the short of the matter,” its author called it – was provided in 1963 by Pope Paul VI shortly after his accession to the Chair of St. Peter and it set the tone for all subsequent defenders of Pius XII. “An attitude of protest and condemnation,” he said, “…would have been not only futile but harmful”; the wartime pope would have been guilty of unleashing “still greater calamities involving innumerable innocent victims, let alone himself.” Of equal pithiness, but never on so high an authority, has been the irremovable reply of Pius’s detractors, who have argued that in the historical context of how the Holocaust unfolded it is all but impossible to conceive of anything worse than what actually happened. Both of these positions had solidified by the mid-nineteen sixties. They had arisen in a storm of polemics let loose by the 1963 appearance of a stage play, The Deputy, a dramatization of the papal silence written by a young German playwright named Rolf Hochhuth, whose raw outrage caught the world’s attention. Before long, however, one of the subtlest of the pope’s critics, historian Leon Poliakov, declared that one could go on forever debating whether Pius’s policy caused more harm than good or vice versa. He noted that the only thing certain was the silence itself “at the most tragic moment of modern history.” The pope, he suggested – later to be joined by some Catholic writers – should have lifted his voice simply because it was the morally right thing to do whatever the consequences, and he left it to historians of the future to make better-informed judgments once the archives of the Vatican were opened. That meant waiting out the Vatican’s fifty-year-rule for unsealing its documents, but so intense was the clash of indignation that Pope Paul announced in 1965 that all of the archives concerning World War II would instead be made public, and a period of watchful expectation brought a measure of calm to the fray. Over the next twenty years thousands of wartime papers were indeed published in a collection of twelve volumes that completed the project, though even the Vatican admits that the work was selective, “edited,” one spokesman assured us, “according to exact scientific standards.” In addition, independent researchers produced a concurrent and far more voluminous outpouring of scholarly works and analyses of more or less exactitude on both sides of the issue. In any event, those future historians, now filling the empty chairs of the old debaters, came brimming with new information, but were still a long way from ready when the matter flared up again in the nineties. In a major policy departure, Pope John Paul II in 1996 acknowledged and later apologized for a failure in which the number Catholics who opposed the Nazis was “too few,” but he went on to formulate the strongest defense of Pius XII yet by advancing the case not only for his earthly ministrations but for his canonization as well. He had in fact planned Pius’s beatification – the penultimate step to sainthood – as a central event of the Holy Year, 2000, but because of the new uproar concluded that it would be more prudent to postpone it for a lower-profile moment after the Jubilee. As for Poliakov’s future historians, they were left in a limbo. At this late date the issue of whether the papal silence was more harmful or less, when based on the thrust and parry of mere documents, seems thoroughly exhausted no matter how many secrets are still to be unlocked from the Vatican’s archives. The reason is clear. The fine-tooth comb had already been applied for more than three decades: the strongest documents in support of Pius surely have already seen the light of day and if there had been anything irreparably damning, it would have long ago sapped the powerful forces within the Church seeking Pius’s sainthood. John Paul II is nobody’s fool and he has staked his legacy on his predecessor’s elevation. On the other hand, today’s information-loaded historians, and for that matter, playwrights and ponderers in general, are in a more advantageous position than ever to wonder in the sublime arena of what if. Rather more information is extant, for example, about the two known crisis-moments in which it appeared that Pius XII, taking pen in hand, would in fact speak out, only to revert to silence in the end. If ever public protest would have made a significant difference in the outcome of events, its greatest impact would have probably been felt in either of those two situations. Testimony before the Vatican secret tribunal examining the case for Pius’s sainthood provides a vivid account of the first of these two crises. It was given by Mother Pasqualina, the German nun who played a major role in Pius’s life both before and during his papacy.

It is the summer of 1942. There has already been a series of Nazi atrocities in Eastern Europe, the work of the Einsatzgruppen mobile killing units. Indeed, well over a million Jews are already dead, and though the events, not to speak of the figures, are imprecisely known to the outside world, the Western media have been reporting eyewitness accounts of hundreds of thousands slain (the Boston Globe, June 26th: “Mass Murders of Jews in Poland Pass 700,000 Mark”). Nevertheless, the “Final Solution,” the actual decision to exterminate all of Europe’s eleven million Jews, is only months old. The vast bureaucratic matrix as well as the state-of-the art technology of cost-efficient genocide, though in prototype stages for years, has taken all this time to gear up. The newly built killing centers – the six camps designed as assembly-line, death-only facilities – have only now begun to run at capacity, feeding on the July-August deportations from France and the Netherlands. A machine has been invented and is running in which you get off a train in the morning and by nighttime the ashes of your existence are dumped in a river and your clothes are packed for shipment to Germany, not to speak of your hair and gold fillings. In short, the world is on the cusp of what in the coming months will become the bloodiest time in all of history. In the outside world by now, the size of the deportations can no longer be kept secret and the fate that awaits the victims is becoming less and less blurred – to all but the victims. Inside the Vatican, that fate is known. The pope, according to Mother Pasqualina, has just received word that in response to a fiery protest by the Dutch bishops against the deportations, the Nazis have retaliated by rounding up 40,000 Catholics of Jewish origin. “The Holy Father,” she stated, “came into the kitchen at lunchtime carrying two sheets of paper with minute handwriting. ‘They contain,’ he said, ‘my protest [to appear] in L’Osservatore Romano this evening. But I now think that if the letter of the bishops has cost the lives of 40,000 persons, my own protest, that carries an even stronger tone, could cost the lives of perhaps 200,000 Jews. I cannot take such a great responsibility. It is better to remain silent before the public and to do in private all that is possible.’ … I remember that he stayed in the kitchen until the entire document had been destroyed.” . I suspect that many historians when reading this testimony, released in 1999, felt a bit of a cringe, uncomfortable with the improbable touches of domestic color and the lapidary kitchen-talk attributed to the pope. Some who looked back at the record found both figures cited wildly wrong: the 40,000 Catholic-convert deportees of Mother Pasqualina’s recall, for one, were at that time actually ninety-two and never more than 600. Nevertheless, the incident of the bishops’ protest has long been known and there is no reason to doubt Pius’s most informed advocate, Peter Gumpel, the Jesuit historian constructing the case for beatification for the Vatican’s Congregation of the Causes of Saints, when he tells us that the pope, on that occasion, was indeed on the verge of issuing a public protest against the persecution of Jews. At the last moment, says Gumpel, when news reached him of the Nazi response to the Dutch bishops’ initiative, he concluded that public protests only aggravated the plight of the Jews and he burned the only copy of his text, four pages long, he says, not two. Before rescuing that text from the flames of reality and sending it on to the Vatican newspaper L’Osservatore Romano for publication to see what might have happened next, let us review Pius’s second chance. Now it is a year and a season later, October 1943. The overall peace-seeking strategy, including the policy of silence, has not gone well for the pope, and he has seen or heard unimpeachable reports that Jews are being put to death at the rate of 6,000 a day. The Allies, with the war turning in their favor, are all but ignoring Vatican diplomacy, toughening not softening their stance on Nazi Germany. There can be no separate peace in the West, they have repeatedly proclaimed, only unconditional surrender. Worse, in terms of the papal strategy, Mussolini has fallen, arrested by the king; the new Italian government has switched to the Allied side and Hitler, enraged as never before, has sent twelve divisions down the peninsula, blasting his way into Rome to occupy the city. Although the Holy See has received assurances from Berlin that its extraterritoriality will be respected, the periphery of the Vatican city-state is ringed with German troops. Still worse, Rome’s Jews have been targeted for deportation to Auschwitz and the pope, though not the target, knows it. The policy of silence is about to be put to its severest strain. On October 16th, Adolf Eichmann’s raiders strike at dawn in the very heart of Rome. In a house-to-house sweep of the ghetto and twenty-five other Nazi-designated “action-precincts,” 365 SS police, over the next several hours, seize more than a thousand Jews, many carted off in the line of sight from the pope’s own windows. Never before has a Supreme Pontiff been so affronted. In an unprecedented diplomatic maneuver, hastily arranged that very morning, Pius authorizes a resident German bishop to threaten Berlin with a papal protest. A letter is drafted for transmission to the Nazi Foreign Office in which the prelate appeals with “great urgency” for an immediate suspension of the roundup. “Otherwise,” he warns, “I fear that the Pope will take a position in public as being against this action.” The explicit threat, again unprecedented, is delivered that afternoon by the pope’s personal liaison to the occupation High Command. Although at this hour, the raid is in fact over, a follow-up dispatch – solicited by Pius’s Secretary of State – is sent by the German ambassador to the Holy See. He confirms that the bishop is speaking for the Vatican and recommends soothing the papal displeasure by using the Roman Jews for labor service inside Italy. The confrontation between Pope and Fuehrer has never been more sharply drawn and all that is left is the question of who will blink first. One week later, the same German ambassador, assessing the post-roundup mood in the Vatican, reports again to the Foreign Office. “The Pope,” he writes, “although under pressure from all sides, has not permitted himself to be pushed into a demonstrative censure of the deportation of the Jews of Rome.” Pius, he concludes, “although he must know that such an attitude will be used against him…has nonetheless done everything possible even in this delicate matter in order not to strain relations with the German government and the German authorities in Rome.” As for the thousand Jews snared in the net, not only have they already detrained at Auschwitz, they are, with few exceptions, already incinerated. Their fate will be shared by another thousand Roman Jews, seized catch-as-catch-can before the occupiers would withdraw, but as the ambassador’s second dispatch predicted, “this matter, so unpleasant as it regards German-Vatican relations, has been liquidated.” Securely buckled up in our what-if machine, we now travel back first to that awful summer of ’42, touching down on the marble floor of the Vatican kitchen. It should not be too hard – knowing all that we do in our time – to respectfully persuade the Holy Father not to set his protest aflame but to let it roar. Having an “even stronger tone” than the Dutch censure, it is addressed to all of the world’s Catholics (then a half-billion), including of course thirty-five million Germans. It is a clear denunciation of the deportations and genocidal fulfillment of Hitler’s pledge to annihilate the Jews of Europe. Apart from appearing in the Osservatore Romano, it is broadcast worldwide by Vatican radio and, wherever possible, read by bishops to their congregations, revealing to the world’s Christians and Jews – and most importantly, Europe’s Jews – that what has been cast by the executioners and their defenders as Allied propaganda is indeed true: a whole people is marked for extinction. Providing credible confirmation of the Holocaust in the making, Pius has thus done what he was being urged to do, particularly throughout 1942, on both sides of the Atlantic. Moreover, he has transcended the skittishness of the Western powers to take concrete steps to alleviate the effects of the persecutions. With the one-way deportation railroad to the killing camps operating at its peak, movements are under way in the Allied countries to devise means of rescuing the intended victims. They are making little headway, but now that Pius has launched his protest, the escalation of public outrage is manifold, tearing down the wall of apathy. In the U.S., for example, the July rally in Madison Square Garden, the December “Day of Mourning and Prayer” and, the April 1943 bilateral U.S.-U.K. rescue conference in Bermuda end not in hortatory appeals or, as in the Bermuda event, utter failure, but with specific plans, ranging from relaxing immigration restrictions to bombing the railways to the death camps – and later the camps themselves. Hitler, to be sure, is incensed. Privately he rages (as he would in fact rage a year later) that he has no qualms about breaking into the Vatican “to clear out that gang of swine.” For now, however, the papal enclave, though under the protection of his fellow dictator Mussolini – who will remain in power until July 1943 – is well beyond the Fuehrer’s reach. Any notion of an Italian government, Fascist or not, marching on the Vatican is inconceivable. The Fuehrer cannot vent enough of his anger by killing many more Jews than his daily 6,000 (the five-fold increase in the slaughter envisaged by Mother Pasqualina’s Pius in the kitchen, or anything like it, is simply organizationally impossible at this stage in the war); nor does the idea of persecuting Catholics solely on the basis of their religion appear very attractive. Roman Catholics, woven in every fold of German society, comprise one-third of the Reich’s population, including Hitler himself. He is therefore faced with two choices: either scaling back the Final Solution or ignoring the pope and the mounting cries for rescue. The scaling-back option is not as unlikely as it might seem. In August 1941, after resounding protests by the German clergy, Hitler halted the Nazi euthanasia program – the “mercy” killing of the incurably sick – and since then (and throughout the war), every time high Church officials strongly intervened in specific cases, he took a backward step from the carnage. These precedents, however, fall short of the magnitude of the present provocation, so we must assume that his fury is such that he chooses the second alternative and, while surely increasing his enemies list, he stonewalls. Whatever additional censorship and psychological browbeating are undertaken by his propaganda minister, Josef Goebbels, to deepen the benighted isolation of the German people, if possible, the tsunami unleashed by the evaporation of the credibility question cannot be stemmed. Planned Allied air-drops of millions of leaflets over Germany informing the people of the extermination of the Jews now go operational with the substitution of Pius’s protest, and any lingering doubts of its authenticity in the minds of Catholics inside the Reich are stilled by nation’s priests. Internal resistance grows. The admonition printed in the paybook of every German soldier to disobey an illegal order begins to take on meaning. The highly placed and unbelievably patient circle of anti-Nazi conspirators, whose various schemes to assassinate the Fuehrer are finally being activated, broadens and is emboldened. But the greatest service that the pope has performed, earning him everlasting gratitude, is to have sounded the alarm to those Jews most in jeopardy, significantly altering the character of their response. Until now, wherever Jewish communities are threatened they have almost invariably sent their leaders forward to petition the Nazi juggernaut with feckless strategies aimed at negotiating a less-than-final solution. These often ad hoc Jewish Councils, as they came to be called in many languages, would establish an abysmal record of failure and, in spite of usually irreproachable intentions, bequeath a dark side to the Holocaust, scarred with compliance, assistance and abject collaboration. One of their most fatal miscalculations is the suppression wherever possible of Jewish armed resistance, but Pope Pius’s revelation of what lies in store for all Jews, ranking or otherwise, has not only removed the very rationale of the Jewish Councils but has given life to what our hindsight has shown as the only sensible response to the implacable foe, fight-and-flight resistance. Thus attempts to crush the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto rebellion and uprisings in the death camps (notably Treblinka, Sobibor and Auschwitz) are carried out against greater odds and with less resolve and some succeed. Contemporaneously, the Allies, yielding to public opinion, bomb Hitler’s death-camp railways and finally the gas chambers themselves. Eichmann’s deportation organization bogs down. Authoritatively warned, Jews wherever possible scatter, taken in by the Allies and neutrals, like Switzerland – all of whom have eased their immigration policies, again, under the pressure of the moral chain-reaction begun in Vatican City. Future projects such as the roundup of the Jews of Rome in the presence of this protesting pope are as unthinkable as is the late-in-the-war deportation of 430,000 Hungarian Jews. In end, true, one must speak of a holocaust, but the Final Solution has failed. We will not be too far from truth if we adopt an estimate that of the six million Jews it would have claimed and the five million non-Jews – Gypsies, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Russian prisoners of war and political, homosexual and other declared pariahs – who would die with them, as much as ninety percent have survived. If we home in precisely on that standoff moment when Berlin has been threatened with a papal protest over the roundup of the Roman Jews, inside the Vatican – where the pope, again persuaded by what is known in our day, is already drafting his condemnation – the situation is as follows. At least 1,023 of those captured in the morning’s raid – one-third of whom are men and two-thirds women and children – are being held less than a kilometer from the pope’s study, awaiting the train of boxcars that will transport them to Auschwitz. For some days now, because of a blunder on the part of a high Nazi diplomat in Rome, he has known the exact language of what lies in store on disembarking. On October 6th, the acting head of the German embassy, young Consul Eitel Moellhausen, in a noteworthy attempt to forestall the coming roundup, sent a message to the Foreign Minister and used the term “liquidate” when speaking of the Jews in question. This was the first time someone in the Foreign Office had used so naked a word in an official document, and news of the consul’s misstep has been leaked to the Vatican. The pope is also aware that the train that will carry off the Roman Jews is already in the nearby Tiburtina rail yards being assembled for imminent departure. Seeking maximum effect, he therefore issues his protest now, publishing it in the L’Osservatore Romano and all other media at his command. The impact of a papal protest in the fall of 1943, though obviously not as life-saving as in mid-1942, has many of the same general features already depicted, thus giving Jews wherever they may be in the remaining danger zones, particularly Hungary, greater chances for survival. Even if it is too late to prevent the departure of those Roman Jews, everyone of whom believing that he or she is headed for a labor camp, with the truth out, the several opportunities for escape that arose during their historical five-day journey to Auschwitz are not now completely ignored. The essential difference between the 1942 and 1943 predicaments is the Fuehrer’s dilemma, the outcome of which will determine the fate of the hero-pope himself. When Pius’s defender Pope Paul VI, as quoted above, spoke of a papal protest victimizing additional innocents, he included Pius as well (“let alone himself”). He was undoubtedly referring to Hitler’s long-known, though weakly documented plan to arrest the pope, some versions of which add a provision for his being “shot while trying to escape.” The most recent rendering to come to light lies among the sainthood documents, in an affidavit taken from former head of the SS in Italy General Karl Wolff. During the occupation of Rome, he says, he was asked by Hitler to draw up a detailed operation for the pope’s arrest and transfer to the Reich, a captivity for which there are in fact two historical precedents (in the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries). Wolff, like Goebbels in July 1943, takes the lion’s share of credit for dissuading his Fuehrer from implementing such a plan, but neither effort required extensive argument beyond pointing to the inevitable backlash. The present, public-protest situation, with the stakes immeasurably higher, is barely comparable to the real event but manifests much greater difficulties in imagining any benefit Hitler might derive: only a silent pope can be blackmailed into continued silence. If Hitler manages to douse his fury, he is left in the same position as he was in the 1942 scenario (scale back or ignore), facing more or less the same consequences. If, however, he loses it, so to speak, and kidnaps (not to speak of martyring) this Vicar of Christ who has lifted his voice and shaken the skies, well, we can feel safe in concluding that the ensuing backlash will make the Ten Plagues that rained down on the pharaoh of Jewish slavery in Egypt look like confetti. The further out one moves from the single event, historian Stephen Ambrose wrote in his essay in the first volume of the What If series, “things get extremely murky, as they always do in what-if history…” But, like Professor Ambrose, that shouldn't keep us from taking one last look in our clouding crystal ball. History records that the extermination of the Jews was stopped six months before the war was over, when Reichsfuehrer Himmler, realizing all was lost and contemplating his own survival, ordered the killing machines dismantled. In our conceit of what might have been, not only the Holocaust but perhaps the war itself would have ended sooner. Such an outcome would undoubtedly have rippled through the rest of history, changing it day by day, we dare not ask to what – the Ambrosian murkiness of history’s outer space being the price of admission to our game. |

| Home | About TheBoot | About Robert Katz | Forum | Issues | Time Capsules | Edizione Italiana | Contact TheBoot |