The Talented Doktor

Dollmann

German spy,

conspirator, secret envoy to the Vatican and the Allies, SS Col. Eugen

Dollmann remains a major source of our knowledge of many  of

WWII’s most dramatic moments. Wherever crisis struck, it seemed, somehow

Dollmann was there or on his way, peering over the shoulder of history

and taking notes. Dismissed in polite conversation as a prevaricator

by many of the same renowned scholars who cite him in their works, his

revelations have stood the test of time. When I first met him, in 1965,

he had already revealed his major secrets - but not all: his mission

to warn Pope Pius XII of the impending Nazi bloodbath in Rome's Ardeatine

Caves. That, too, has been upheld. In 2000, many years after his death,

the CIA released documents that confirmed a long-held suspicion that

at war's end he had gone on to serve as a source for Allied Intelligence.

— RK of

WWII’s most dramatic moments. Wherever crisis struck, it seemed, somehow

Dollmann was there or on his way, peering over the shoulder of history

and taking notes. Dismissed in polite conversation as a prevaricator

by many of the same renowned scholars who cite him in their works, his

revelations have stood the test of time. When I first met him, in 1965,

he had already revealed his major secrets - but not all: his mission

to warn Pope Pius XII of the impending Nazi bloodbath in Rome's Ardeatine

Caves. That, too, has been upheld. In 2000, many years after his death,

the CIA released documents that confirmed a long-held suspicion that

at war's end he had gone on to serve as a source for Allied Intelligence.

— RK

The Time Capsule

that follows was first published in the long-defunct American magazine

True, dated April 1967.

ust beyond the Odeonsplatz in Munich, in a curved arid narrow street, there is a small, comfortable hotel painted blue. No one recommends it for tourists. People do not speak English there and when they talk at all it is in whispered tones; the guests prefer it that way. ust beyond the Odeonsplatz in Munich, in a curved arid narrow street, there is a small, comfortable hotel painted blue. No one recommends it for tourists. People do not speak English there and when they talk at all it is in whispered tones; the guests prefer it that way.

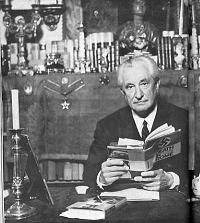

On the top floor, in a sunny chamber with a sloping ceiling, is a faded autographed picture of a Nazi general. The general, dead for many years, looks out from a black past with a smile that never wearies. He sees an ornate room, with damask and silver candlesticks. It is cluttered with books, clippings, other photographs and bundled sheaves of papers that have become the vault of memories. It is a room where 22 years ago time stood still: the attic home of a certain Dr. Eugen Dollmann, formerly Colonel Dollmann of the SS.

At this very moment Colonel Dollmann, his ash-blond hair turned metallic gray, but his eyes as bright as they were when he first met the Führer, is perhaps sitting at his desk, tapping on the typewriter. Others have long ago forgotten their Nazi years. But not Dollmann. Even now he may be grasping for a fleeting thought, trying to snare and set down on paper a recollection of what Himmler said to Goering at a conference on a frigid night in '42. Or he may be thumbing through a new book about the Nazis by someone he knows, like former CIA chief Allen Dulles. Or perhaps the colonel is taking tea with a foreign visitor, a journalist who would like to know why secrets the Führer's mistress whispered in Dollmann's ear one lazy afternoon in Naples before the war.

Who is this Dollmann?

"Dollmann?" an Oxford historian remarked to me on hearing I had been to his garret to see him: "Oh, that old liar!"

But the historian is kidding and he knows it. In his major

book on World War II, he repeatedly cited Dollmann as a source of credible

information. Other writers, including such authorities a H. R. Trevor-Roper

(The Last Days of Hitler) Alan Bullock (Hitler, A Study in

Tyranny) and John Toland (The Last 100 Days) have relied

on the little-known Colonel Dollmann for what we know today about some

of the most crucial moments in Nazi history.

In his various roles as a German spy, conspirator, secret

envoy to the Vatican and the Allies, interpreter to both the Führer and

Mussolini, Dollmann was an eyewitness to an incredible number of drama-filled

moments of crisis, battle and betrayal. Sometimes a mere shadow, sometimes

an audacious commander, he was always a chronicler, storing in his mind

the stuff of tales for tomorrow. He had the uncanny talent of being everywhere

in Nazidom whenever history was being made —a clandestine intelligence

agency unto himself.

"The ubiquitous Dollmann," Dulles calls him "He was an

intellectual, highly sophisticated somewhat snobbish and cynical."

An Italian countess who met Dollmann in German-occupied Rome said: "He was tall, slender and elegant, not at all a German type. With perfect grace, he kissed my hand and invited me to sit beside him ... I hated him!" In the classic anti-war film Open City, director Roberto Rossellini modeled his sadistic "Captain Bergmann" after his image of Colonel Dollmann. Others have called him a murderer, war criminal, and a "fiend of forcefulness."

"His ambition was to be taken for a polite man of the Machiavellian school," says a high German diplomat who tried to help those persecuted by the Nazis. "He had an appetite for intrigue . . . and a wide circle of friends in the highest places, whom he charmed with his inexhaustible talent for sparkling conversation."

Of himself, Dollmann says he was only a bookish man and that after he entered the SS, "my way of life remained unchanged and I rejected enticing offers of luxurious apartments, automobiles from the Führer."

Eugen Dollmann was born in Regensburg, a Danubian town at the edge of the Bavarian Forest, in the year 1900. He was a lawyer’s son, which may account for his flair for the spoken word. On his mother’s side were an Italian prince and a court physician to Empress Elizabeth of Austria.

The family fortune was lost during World War I, but the old titles and blue blood were retained and young Eugen was introduced into the intellectual and social life of Munich and Vienna. He entered the University of Munich, dipped deeply into the history of art, the Renaissance Romance literature, and emerged with a doctor’s degree in the problems of the Reich during the Counter-Reformation.

This was a time of great ferment in Munich. On the evening of November 8, 1923, Adolf Hitler leaped onto a table in one of the city's largest beer halls and drew his gun. He fired a into the rafters, waved his pistol wildly, and shrieked: "The national revolution has begun…” Some months later the young putschist was convicted of treason and sent off to prison. But now he was known to all the world and the people of Munich bristled with excitement.

Dollmann remembers it well. It was then that he first savored

the spice of scandal, learning what he believes was Hitler's "most delicate

secret." (See box)

Was

Hitler a Homosexual? A born-again question answered (again)

On Christmas eve, 1923, while Hitler was awaiting trial, Gen. Otto

von Lossow, who had helped suppress the pocket revolution, gave

a lavish party. Dollmann, then only  a

wide-eyed university student among Von Lossow’s distinguished guests,

recalls the regal atmosphere: an 18th-century parlor lighted only

by hundreds of candles set in crystal chandeliers; beautiful men,

knightly men—the pinnacles of Bavaria's "best families"; a little

orchestra playing softly m the nearby music room; a giant Christmas

tree and conversation that gravitated always toward the fascinatingly

vulgar young man with the toothbrush mustache and his putsch. a

wide-eyed university student among Von Lossow’s distinguished guests,

recalls the regal atmosphere: an 18th-century parlor lighted only

by hundreds of candles set in crystal chandeliers; beautiful men,

knightly men—the pinnacles of Bavaria's "best families"; a little

orchestra playing softly m the nearby music room; a giant Christmas

tree and conversation that gravitated always toward the fascinatingly

vulgar young man with the toothbrush mustache and his putsch.

At this point, as Dollmann tells it, Von Lossow produced a metal

case, which had come from police headquarters. It contained secret

papers about Hitler’s private life since his arrival m Munich more

than 10 years before. The doors to the red and gold parlor were

closed and the servants dismissed. In the muted background the orchestra

could still be heard. The old general pick«d up a folder thick with

depositions and eyewitness testimony. In a cutting, pitiless voice,

he began to read:

"In a café near the university on the evening of…"

When he had finished, his hushed audience had been titillated with

lurid images of a nasty man less interested in German politics than

in young and boyish German men.

No one has ever confirmed the existence of the Von Lossow papers,

let alone whether or not they were falsified. But the staid old

general’s juicy tale impressed Dollmann deeply, whetting his patrician

taste for gossip. This love of paradox and irony would send him

chasing after secrets and scuttlebutt with Casanova's passion. The

knowledge he would gain would help him stay alive in the bloody

era that was dawning.

|

lways

probing, ever querying, Dollmann would one day find a measure of support to the

buried scandal. lways

probing, ever querying, Dollmann would one day find a measure of support to the

buried scandal.

The year was 1938. The time was spring. The place sunny Naples.

Two people alone: a dashing SS man in a trim olive uniform, his cords

and tassels dangling impressively from his shoulder; and a youthful, rather

attractive German fraulein, a girl on a holiday in Italy. His name is

Dollmann; hers, Eva Braun, said to be Hitler's mistress.

Dollmann had spent the past decade in Italy. As a young scholar he had come to Rome in 1927 with a grant to do research on a Renaissance pope. The grant ran out. The world changed. Hitler came to power. But Dollmann managed to stay in Italy, pursuing his studies. By now he spoke the language flawlessly and was known to his many friends as "Eugenio." A year before his encounter with Eva Braun, his rather obscure existence had been completely transformed. He had come face to face with Hitler. They took a liking to one another. It happened this way: Hitler was to address an assembly of Italian Fascist youth. His interpreter was suddenly taken ill. Dollmann was pressed into service and summoned to Hitler's room. "Mein Führer," snapped the stiff adjutant who introduced them, "Doktor Dollmann ist da." One can still hear the heels clicking.

A figure stepped from behind a screen. It was Hitler. He extended his hand.

"So, you are Doctor Dollmann from Rome?"

"Hitler held my hand for several seconds," Dollmann remembers. "He stared at me intensively with those famous eyes... it seemed as if he were trying to hypnotize me."

Perhaps he was, although Dollmann claims he was immune to Hitler's reputed magnetic qualities. In any event, Dollmann immediately entered the elite and sinister, paramilitary Schutz Staffel (SS) . He was given a commission and a "dream job" as SS boss Heinrich Himmler's deputy in Rome, which meant prying into the affairs of diplomats, kings and titled ladies. He was also to be an interpreter at the highest level.

Dollmann had scarcely settled into his new life, when Hitler made a state visit to Italy. Dollmann was given the delicate task of keeping Eva Braun, who was not to be seen in public with the Führer, out of view. So while state banquets at the Quirinal Palace in Rome were being held amid the pomp of royalty, Eva and Dollmann were touring Naples.

He charmed her. It was easy. Eva, the photographer's daughter, pined for a fairy-tale life as one of the heroines in the dime novels and movie fan magazines she read incessantly. She loved dancing, daydreams, and gallant men. Before long Dollmann won her trust and became her confidant. This was but a single step from verbalizing the question in the mind of every German: "What was it like, what was it really like, to be his woman?"

"He is a saint," Eva said to Dollmann a little sadly. "The idea of physical contact would be for him to defile his mission. Many times we sit and watch the sun come up after spending the whole night talking. He says to me that his only love is Germany and that to forget it, even for a moment, would shatter the mystical forces of his mission. . . . The mission, the mission, always the mission! ... Of course, people think of my life with the Führer in quite another way. If they only knew!"

Dollmann, recalling Von Lossow's party, says he knew it all the time.

When that long Italian summer faded, Dollmann turned to more serious work. Hitler was getting ready for war. In September the Munich Pact was signed, virtually wiping Czechoslovakia from the map. Dollmann was there, lolling in the glitter, his mind recording the behind- the-scenes chatter.

The Führer, French Premier Daladier and British Prime Minister Chamberlain put their names to the agreement that was to bring "peace in our time." But, according to Dollmann, the show belonged to Mussolini.

"Whoever observed him that dramatic day," Dollmann thinks back, "could not but admire his talent as an actor."

When the war exploded, Dollmann stayed in Rome. His work grew more complex, dangerous—with Dollmann loving every minute of it. He dabbled in espionage, spying for Himmler on Germany's ally, the Italians. He disapproved of the Nazis' heavy-handed police methods, although he never complained aloud. The subtler Italian techniques, formulated by one of his closest friends—Himmler's Fascist counterpart, Arturo Bocchini—were more to his tastes.

Bocchini's spy organization, says Dollmann, was more "refined" than the Gestapo and did not specialize in wholesale arrests and torture. "It kept a close eye on the mistresses of its clients and it bribed prostitutes, pimps, brothel-keepers and aristocrats." "Bocchini," says Dollmann nostalgically, "was the last of the great European police chiefs."

For Dollmann's side the war went well at first, but then, after Stalingrad, the Reich began to crumble. On a hot Roman Sunday in July, 1943, the debonair SS man stepped out of his role as an onlooker to history and tried to make some on his own.

The stunning news that day was the sudden overthrow and arrest of Mussolini by a group of conspirators led by the Italian king and Army Marshal Badoglio. Dollmann rushed over to the German embassy.

"I told our ambassador that he had only two alternatives: either make immediate contact with Badoglio, or take command of the SS brigade in Rome and through me link up with the 'M' Division [Mussolini's militia] and liberate the Duce." Dollmann urged the latter course. He argued that the "M" Division's 36 Supertiger tanks would be enough to sweep Badoglio away and restore the Nazis' longtime spiritual ally to power. In the meantime Berlin was continuously on the telephone. Hitler screamed that Badoglio must not be recognized and demanded that Mussolini be freed. Dollmann's plot offered the way, and he and Ambassador Hans Georg von Mackensen waited for the overthrown Fascist leaders to gather around them for the march against Badoglio and the king.

At 9:15 that evening one lone Fascist appeared: party boss Roberto Farinacci. Dollmann thought the moment for the countercoup had come. He swiftly ushered Farinacci into the ambassador's suite, away from the cries of the joyful but threatening crowds who had filled the streets of Rome.

"Farinacci's face had paled and he trembled with fear," Dollmann recalls. "His only wish was to take the first plane to Germany. Not a word about the Duce. Not a word about the 'M' Division. Not a sign that he wanted to attempt the liberation."

Dollmann was disgusted. No one else ever showed up. The plot failed. Hitler was furious. Mackensen was recalled to Berlin. But the indomitable Dollmann somehow won a promotion to Standartenführer, a full colonel. If you don't know what the duties of a Standartenführer in Rome might be, it is not surprising. Neither did Dollmann. But it sounded fine and he used his title to extend his self-appointed powers and his ever-growing influence.

Exactly one year later, almost to the day, he was to see another conspiracy go bad. In this one, the July 20th plot to assassinate Hitler, he had no part—other than a privileged front seat at the aftermath, where he was an eyewitness to some of the most bizarre and emotionally charged moments of the war.

At about 12:40 p.m., a bomb concealed in a briefcase went off in Hitler's conference room. Hitler was but a few feet from the tremendous blast. The walls and windows and several German officers were blown apart, but the Führer escaped serious injury with not much more than a scratch, although his eardrums were damaged from the sound of the powerful explosion.

By a strange coincidence Dollmann showed up a few hours later—some 2,000 miles away from his home base. He was accompanying Mussolini, who months back had been rescued by Hitler's agents, and reinstalled at the top of a shaky puppet regime. Hitler and Mussolini inspected the bombed-out conference room, with Dollmann peeking over their shoulders. A few hours later a mad tea party was held. Hitler raved thunderously—right into Dollmann's memory tape—about how he would wreak bloody revenge on the plotters. ("I will sweep them off the face of the earth. . . .") Dollmann was terrified. He had never seen or heard anything like this.

His 10-page account, typed out while he was a prisoner

of the British after the war, formed the basis of what the world knows

about that singular afternoon. The story has been retold endless times

in countless books (sometimes, Dollmann decries indignantly, "without

acknowledgement"), including the Trevor-Roper and Bullock histories, and

William L. Shirer's The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich.

The July 20th plotters, Dollmann said years later, "tried to do too much too late." He himself, even as he listened to the vampire Führer searching for the plotters' blood, was already involved in a conspiracy of his own. Though he did not know it at the time, this would end in the "secret surrender" to Allen Dulles of the million-man German army in Italy.

Whenever he tells the story of the surrender in May 1945, which he does quite frequently, Dollmann begins with May.1944. Then, in an atmosphere of high intrigue, he arranged a top- secret meeting between SS-Obergruppenführer (Gen.) Karl Wolff and Pope Pius XII.

Always creating glamorous roles for himself, Dollmann had stepped into the: part of a Nazi liaison with the Church. Only six weeks or so earlier, he was involved in a significant meeting at the Vatican. A group of Italian partisans attacked a column of SS men, killing 33. Hitler, in a rage once again, demanded that 50 Italians be shot for each dead German, though the field commanders reduced the ratio to 10 to 1. The executions were carried out. in the Ardeatine caves of Rome.

In researching my book Death Rome, which deals

with the massacre, I was told by Dollmann that he had alerted the Vatican

to the Nazi plan. The lack of intervention by the Church has added fuel

to the controversy over the Pope’s role in World War II.

In the Rome of 1944, then, Dollmann had come to know Vatican dignitaries well. The Pope agreed to see General Wolff, especially since high-placed Italian friends of Dollmann's were hinting that the audience might somehow be aimed at peace. Wolff, however, was not yet a full party to Dollmann's dreams and intrigues.

On May 10th, Wolff, dressed in borrowed civilian clothes, was spirited into the Vatican and directly to the sala delle udienze of His Holiness. While Dollmann waited in the antechamber, Pope Pius XII and the Nazi general spoke for three-quarters of an hour. There is no record of what was said, other than Dollmann's word and the account given in Wolff's still unpublished memoirs, which were ghostwritten by—you guessed it—Dollmann.

In these papers Wolff, that is, Dollmann, wrote that in the course of this audience: "I declared myself ready to do everything in my power to bring the war to a rapid conclusion." Even Hitler would have said that. But even Hitler probably would not have committed the horribly gauche little incident that occurred as Wolff was taking leave of the Pontiff.

The door to the private room opened and Dollmann could see Wolff backing away from the gaunt Pope. Instead of bowing politely or performing some such nicety, the SS so-called "peace" general suddenly stiffened. Obviously obeying an ingrained reflex mightier than his will, Wolff's right arm shot up in a Nazi salute: "Heil Hitler!" Dollmann looked on in cringing amazement, his skin crawling.

Less than a month later Rome fell to the Allies and Dollmann fled with the retreating German armies to the north of Italy. At the same time the D-Day invasion penetrated the heartlands of Hitler's Fortress Europe, and the Russians continued their inexorable sweep westward. Dollmann, like many of his Nazi colleagues, knew the time was rapidly approaching to have to make "peace"— the word "surrender" did not enter until much later.

The peace the Germans hoped for was an East-West split in the Allies, a separate peace with the Anglo-Americans, and an all-West campaign against the Russians. "An absurd idea," Dollmann said later, but not then. While Germans in the east, west and north were conjuring plots of their own, the Nazis to the south looked to Dollmann to get an Italian- based conspiracy rolling, which was the one that eventually was first to pay off. Now was the time to bring "peace general" Wolff really into the picture. But Dollmann made the mistake of mentioning the plot on the same day the attempt was made to kill Hitler. The bloodbath that followed the July 20th affair, was enough to scare off Wolff for another nine months, until March, 1945.

At last he did enter Dollmann's conspiracy. Negotiations were opened with Allen Dulles. The rest is history. In the end, the German dream about breaching the unconditional surrender terms was discarded in the face of the tough reality that the Germans had lost the war. The Allies held fast. Hitler killed himself, freeing his officers from their oath of loyalty to him. The Dollmann-to-Dulles capitulation took place on May 2nd. Six days later the war in Europe was over.

When the big news broke, Dollmann was enjoying the peaceful sunshine in a northern Italian villa. He felt somewhat immune to the world's hatred of the fallen Nazis. For his role in the surrender, he had been given vague assurances of special consideration by the Allies.

On May 13th, however, he was arrested. A new life of adventure was about to begin.

In British custody he was moved to Rome to an interrogation center hastily set up in some movie lots where in what were suddenly "the old days" Dollmann had sipped champagne at parties of the queens of the European screen.

Among his prison mates was Frau Himmler, of course a dear friend of Dollmann's. He thus recorded for history her famous remark on hearing of her husband's suicide: how happy she was that Heinrich would not have to hear the bad things people were saying about him.

The British cleared Dollmann of any war crimes responsibility and he was transferred to a POW camp. One night, between the sweeping searchlights from the guard towers, he cut through the barbed wire and escaped. He made his way north, contacted the Archbishop of Milan (another old friend). Moved no doubt because it happened to be Christmas eve, the prelate found a hiding place for the fugitive in the Cardinal Ferrari Institute, a mental institution.

Dollmann lived among the patients for several weeks, embittered by the "raw deal," the Allies had given him. Then, much to his surprise, he was invited to come to Rome under American protection. His unseen sponsors set him up in a luxurious five-room apartment in the best part of town. For weeks he wondered in silent ignorance about his turn of luck. Finally he was visited by two American intelligence agents. They provided him with a new identity (he was now "Alfredo Casani"), a bundle of banknotes and an assignment as an undercover spy for the U.S. to engage, he says, in "anti-Russian espionage." A new, cold war was on.

Dollmann switched sides as easily as changing TV channels. But before he could be given his first mission he was— in the words of the trade—"blown." Recognized outside a movie theater by an ex-member of the underground, he was arrested by the Italian police. The story of the top Nazi living in luxury in Allied Rome made world headlines and embarrassed Washington. His usefulness as a spy was reduced to zero. He was dropped.

To remove Dollmann from the hostile Romans, the Americans arranged his release, later sneaked him out to the airport on a stretcher and flew him to Germany. He tried to go to Austria and was promptly rearrested by the French, whose occupation zone he was in. Again the Americans stepped in and gained his release. A U.S. secret agent, Irving Ross (who was later mysteriously killed), stuffed Dollmann into the trunk of his Cadillac and drove across the Italian border.

With the help of his friends in northern Italy, Dollmann was admitted to Switzerland. He was later handed an Italian passport, of dubious authenticity, in exchange for his help in setting up a clandestine aid service for the many Nazis who had a sudden postwar interest in getting to South America. This activity, which seems to have kept him occupied for a number of years, had another name: something probably said with a devilish smile, like "refugee relief work."

Early in 1952, the Swiss opened deportation proceedings against Enrico Larcher, a Milanese art dealer who proved to be none other than Dollmann. In October Larcher, or Dollmann, showed up in West Germany at the Frankfurt airport and was arrested by immigration officials. He was reportedly linked to an undercover Nazi movement based in Madrid with far-flung operations on three continents.

The press was loudly indignant for a while, but in the end Dollmann was convicted only of traveling on forged documents and served two months in a West German jail. Since then, he has been out of the news, at least off the front pages

Today, at age 67, still lithe and dapper, looking a full decade younger than his years, Dollmann appears to be retired. A colonel's pension eases matters. He has had time to pen his wartime memoirs and even those of some of his colleagues, too. Now he is working on an autobiography, bringing the story up to date.

The last time I saw Dollmann, a couple of months back in that ornamented garret in the blue hotel, I asked him about his present activities. "I deal only in times gone by," he replied, "writing, television appearances occasionally, and reminiscing."

But Dollmann claims to be an authority only on "times past," and he is but incidentally interested in the present, less so in the future. In that event, has he told all he knows? Are we to expect new revelations, which may prove meaningful to history? And most important, has he told the truth?

Undoubtedly there are some secrets he will never divulge. Others may come out, as has already happened, if he outlives the persons involved. There may be something new in the Dollmann-ghosted Karl Wolff memoirs, if they are ever published. (Wolff. incidentally, is now in prison, convicted in 1964 for his part in the extermination of 300,000 Jews.) I have seen in those pages a noteworthy quote attributed to Hitler concerning the still-disputed Hess case. Here, according to Wolff-Dollmann, the Führer virtually admits that he sent Hess on his famous flying peace mission to Britain in 1941. If so, this would overturn the existing consensus that Hess acted alone—out of madness. Dollmann says today: "Hess was not mad; a very highly placed source told me at the time he was 'fully convinced' Hess was sent by Hitler."

As for the marriage of Lady Truth with Doctor Dollmann, time will be the best judge of that relationship. In my own experience, wherever it was possible to consult other sources his version of events was for the most part corroborated. Others have found him usually reliable, but given to exaggeration.

Where he is most refreshingly faithful to the way things really were, is in his refusal to deny that he was just as much a Nazi as any other member of the party. Perhaps the best description of what kind of Nazi he was came out of our most recent encounter.

He had learned that Alien Dulles in his book on the surrender had called him a "slippery customer" (actually Dollmann had misread; it was one of Dulles's aides who had used the phrase). Dollmann seemed upset. "From the little English I know," he said in beautiful Italian, "sleeperee coostomer is not exactly a compliment. Is it?"

I said it meant someone who was shrewd, cunning, Machiavellian.

"Oh," he observed suddenly beaming, "that is a compliment—for me."

Copyright

© 2008 by Robert Katz

|